Your

old analog camcorder may have been consigned to the closet since your

three-hour family vacation movie five years ago, yet it still has

more facilities than a thousand dollar digital still camera.

Your

old analog camcorder may have been consigned to the closet since your

three-hour family vacation movie five years ago, yet it still has

more facilities than a thousand dollar digital still camera.CAMCORDERS AS DIGITAL STILL CAMERAS

by John Henshall

It is often the seemingly amateur devices which tempt and inspire professionals to try new things. For, although the plethora of low-resolution digital cameras will not displace our Nikons, Hasselblads and Sinars, each development brings new facilities to another professional niche and keeps us aware of the way things are moving.

Most of the digital still cameras now hitting the market have resolutions which are far too low for magazine repro work. At 250 ppi, a 640 x 480 pixel image will reproduce at only 2.5 x 2 inches. But at 72 ppi, 640 x 480 pixels produce on-screen images of over 8 x 6 inches - big enough for most images on the web - and this is tempting web designers to use them as convenient alternatives to film. The problem is that, no matter how much manufacturers hype their technological advanced interiors, in serious photographic terms these cameras are no more use than a Box Brownie.

Although innovation has abounded, not one product has learned sufficiently from the mistakes of others not to make similar mistakes of its own. Who would have thought it possible that, two years after the advent of the first Casio digital camera with a color LCD screen, we would still see cameras which have an unshaded, power-hungry LCD as the only means of composing a shot?

ANALOG CAMCORDERS

Your

old analog camcorder may have been consigned to the closet since your

three-hour family vacation movie five years ago, yet it still has

more facilities than a thousand dollar digital still camera.

Your

old analog camcorder may have been consigned to the closet since your

three-hour family vacation movie five years ago, yet it still has

more facilities than a thousand dollar digital still camera.

Its twenty five or thirty frames per second (depending upon where on the planet you live) continuous motor drive ensures that you do not miss even the most fleeting part of the action - we used this facility to capture Bill Gates' smile at Seybold SF97. Moving images are simply a rapid succession of stills and a US (NTSC) camcorder takes thirty pictures per second. A one hour tape - we could call it 'removable re-usable image storage media' - holds 108,000 images. A ninety minute NTSC tape holds 162,000 images. No digital still camera can boast this feature, though it comes as standard with every camcorder.

A wide-range zoom lens enables you to get tight closeups and expansive wide angles. Macro facility allows you to fill the frame with the new product you want to start promoting on the web right now. A camcorder also has an electronic viewfinder, showing exactly what you are shooting.

You can start by dusting down and using your old camcorder. It is already an electronic camera: like its latest digital still camera cousins, it uses a CCD image sensor to convert light into electrons, instead of using film. The only thing it doesn't have is the section which converts the electronic picture to digital.

AV MACINTOSH

If

you have an AV Macintosh, you already have an on-board digitizer and

only need a connecting cable. If your camcorder has an S-Video output

(a socket about 9mm diameter with four pins and a small rectangular

peg) be sure to use that. S-Video keeps the video brightness

(luminance) and color (chrominance) signals separate, producing

better quality pictures than composite NTSC or PAL video. If you

can't use S-Video, get a good quality RCA phono cable intended to

carry video.

If

you have an AV Macintosh, you already have an on-board digitizer and

only need a connecting cable. If your camcorder has an S-Video output

(a socket about 9mm diameter with four pins and a small rectangular

peg) be sure to use that. S-Video keeps the video brightness

(luminance) and color (chrominance) signals separate, producing

better quality pictures than composite NTSC or PAL video. If you

can't use S-Video, get a good quality RCA phono cable intended to

carry video.

Connect the camcorder, then look for the 'Apple Video Player' application. Select 'Show Controls Window' from the Windows menu and click the monitor icon. Select the 'Video source' you are using (TV/Video/S-Video) then click the camcorder icon. You will see two buttons: 'Freeze' and 'Save'. That is exactly what you do, freeze and save. It could not be easier.

GET SNAPPY

PC

users need a digitizing card, such as Hauppauge Computer

Works Incorporated's Win/TV Primio PCI card for Windows 95 with

built-in tv tuner. http://www.hauppauge.com

PC

users need a digitizing card, such as Hauppauge Computer

Works Incorporated's Win/TV Primio PCI card for Windows 95 with

built-in tv tuner. http://www.hauppauge.com

An easier, neater way is to use Snappy, made by Play Incorporated. http://www.play.com. Snappy is a no-compromise digitising device which plugs into the parallel (printer) port in seconds. The price has been dropped to $95 and version 3 of the capture interface has just been released.

Snappy is a neat design with two recessed blue thumbscrews which secure it firmly to the parallel port. It is light weight but somewhat bulky - 5 inches long x 2.75 wide x less than 1 inch thick. Connect it using a printer extension cable, which also makes it possible to site Snappy wherever convenient to connect the video cables. Apart from the 25 pin connector there are just two RCA phono sockets: one marked 'Video In', the other 'Video Thru'. Video thru loops the pictures from the camcorder through to a television set - easier than peering at the small 160 x 120 pixel preview on the computer monitor.

Snappy

needs a PC with a 486 processor or better, Windows 95/NT3.51 or later

or Windows 3.11, 4MB RAM, at least 8MB of free hard drive space and

an unused parallel port. You can feed video in from any source - even

a VCR. Remember, though, that VCR resolution is poor and images will

look soft and smeary. Snappy is powered by a standard 9 volt internal

battery, said to be good for around a thousand snaps.

Snappy

needs a PC with a 486 processor or better, Windows 95/NT3.51 or later

or Windows 3.11, 4MB RAM, at least 8MB of free hard drive space and

an unused parallel port. You can feed video in from any source - even

a VCR. Remember, though, that VCR resolution is poor and images will

look soft and smeary. Snappy is powered by a standard 9 volt internal

battery, said to be good for around a thousand snaps.

Snappy captures 640 x 480 pixel images, the quality of which depends on the quality of your video source. It will also over-sample a sequence of images from a static source, though the improvement in quality using this technique is difficult to see.

Snappy is a productive, inexpensive product which is easy to use. The only drawback is the delay between clicking snap and the frame you capture, which makes grabbing frames from moving subjects somewhat hit and miss.

Version 3 of the software has just been announced for the American/Japanese (NTSC) tv standard, looking as though it has been redesigned by Kai Krause. It has a 'live' color preview and a shorter snap to capture delay. The new PAL version is expected mid-1998.

DIGITAL IS BETTER

In the last decade or so, the word 'digital' has become synonymous with 'better'. Audio CDs replaced crackling phonograph records, giving us studio quality music wherever we desire. Word processors replaced typewriters, adding a host of new facilities. But athough today's digital compact cameras look like their film counterparts, they do not produce such high quality pictures. Not even the latest megapixel digital cameras have anything like the resolution of film. In digital imaging the old cliché, "A picture is a thousand words," is way out - a digitized 35mm frame would take up the same computer space as three million words. In short, digital imaging is a hard nut to crack at a reasonable price. Only the top price digital camera backs come close to film quality. One or two even exceed it.

Television has never enjoyed the same quality as its cousin, the motion picture shown in a movie theater. Television is shown on a small screen, so quality has not been so important, and fortunately the human brain interpolates when the picture is moving. When VCRs became popular around twenty years ago, we tolerated the poorer quality because the facility to record programs was so useful.

Camcorders have enabled us to capture, preserve and share important family and business moments, not with broadcast quality but with quality 'adequate' for the purpose.

DIGITAL CAMCORDERS

JVC, Panasonic, Sharp, Sony and now Canon all have 'DV' - Digital Video - camcorders. More are in the pipeline. These cameras produce pictures much sharper than their analog counterparts - so good that the quality of the best of these cameras and their built-in recorders now rivals the professional format, Digital Betacam. The video tape recorders in DV camcorders record digitally - in effect, they're like digital tape streamers, using a cassette similar in size to DAT. DV pictures are also better because the luminance and chrominance signals are kept separate.

Sony's top-of-the range DV cameras, the DCR-VX1000 and DCR-VX9000 (around $6,000) and Panasonic's new NV-DX100 (around $4,000) use three CCD chips to analyze the image into its RGB components, just like broadcast tv cameras. No digital still camera does it this way. The quality is stunning.

I use the Sony DCR-PC7 (under $2,000), which has a single CCD but has the advantage that it is pocket-sized, so I take it everywhere. I would soon tire of carrying a larger semi-pro model around. The PC7 has become my digital notebook, with pictures and stereo sound. It sat it on the table at Seybold SF97 and it captured images of all fourteen speakers at my sessions. You can see the images from the tapes at http://www.epicentre.co.uk/seminars/seyboldsf.html

FIREWIRE

Digital imaging is often regarded as truly instant photography and there is no doubting its convenience if you need just one or two images in a hurry. Unfortunately it takes almost as long to upload a camera-full of images via the computer's serial port as to pop into the local minilab and put a roll of thirty six exposure film through the one hour processing service.

Snappy will digitise the analog outputs from digital camcorders, of course, but since they are already digital, it is best to keep them that way and acquire them digitally.

One day soon, computers, cameras, scanners and printers will have a new connection interface called IEEE 1394-1995, popularly known as FireWire or, simply, '1394' - though some (Sony included) want to call it 'i.Link'.

FireWire's main advantage is its enormous speed - it will transfer data between devices at speeds up to 400Mbps - about 50 Megabytes per second. An other big advantage is FireWire's ease of connectivity via small thin cables, with tiny connectors and the facility to 'hot plug' devices without powering down the computer. It is also isochronous - able to deliver data at a pre-determined fixed rate. This is essential for applications such as video, which need a constant stream at about 25MB per second.

FireWire is so fast and simple it makes SCSI look like something out of The Flintstones.

RADIUS PHOTO-DV

We

have been using a FireWire card from Radius Incorporated http://www.radius.com/products/

We

have been using a FireWire card from Radius Incorporated http://www.radius.com/products/

DV_FireWire.html in a Macintosh 8600/250, together with Radius'

PhotoDV plug-in for Adobe PhotoShop, to acquire images from the Sony

DCR-PC7 camcorder. It took five minutes to install the card and

software which worked first time, without any need for configuration.

The speed advantage is immediately noticeably when you acquire

digital stills from a DV camcorder.

The Radius PhotoDV interface has a 180 x 134 pixel color preview, under which is a slider enabling you to set the preview image in one of three positions, from Faster to Sharper. The Mac 8600 is fast enough to use the sharper setting at all times. Below this are buttons for remote camcorder control of normal Play, Search (for next shot change), Fast Forward and Rewind (at 12x speed with picture - in effect searching 300 digital images per second or 90,000 625-line images in five minutes), Slow play forward and reverse at one-tenth speed (2.5 frames per second), and Step (one frame at a time) in both forward and reverse. It took less than six minutes to search all 90,000+ images of Bill Gates on a 63 minute tape, to find the picture of him smiling. There's no other way to search such an extensive resource so quickly.

Professional

video - and DV - assigns a precise identity to every picture, in

hours, minutes seconds and thirtieths of a second (twenty-fifths of a

second for PAL). Radius PhotoDV displays this frame-accurate 'time

code' in an on-screen box, making it possible to return precisely to

any particular frame. Time and date of recording can also be

displayed.

Professional

video - and DV - assigns a precise identity to every picture, in

hours, minutes seconds and thirtieths of a second (twenty-fifths of a

second for PAL). Radius PhotoDV displays this frame-accurate 'time

code' in an on-screen box, making it possible to return precisely to

any particular frame. Time and date of recording can also be

displayed.

On the left of the interface is selection for NTSC (525 lines 30 frames per second used in USA and Japan) and PAL (625 lines 25 frames per second) and also for aspect ratio - 4:3 (1.33:1) and widescreen 16:9.

Moment in time. Fleeting moments are more easily captured with a camcorder than with a still image camera. Here the author caught Bill Gates smiling during his keynote at Seybold San Francisco by scanning through the video of his hour-long speech.

Capture can be set to One shot, Multiple shots (to save time re-selecting the plug-in) or Auto every 'x' seconds until 'y' images have been captured - useful for time-lapse.

PhotoDV will also capture the raw image from the camera. In 525 line NTSC these images have 720 x 480 pixels, in 625 line PAL the slightly higher resolution of 720 x 576. Normal television pictures have a 1.33-to-1 aspect ratio, so these pixel counts would produce a distorted image on the computer screen, because the pixels in a tv camera are rectangular. Pixels displayed by a computer are square, so images must be interpolated to preserve correct proportions. PhotoDV will do this automatically by selecting its 604 x 454 (NTSC) or 680 x 510 (PAL) 'Square' settings. These settings also crop pixels from each edge of the image, to compensate for cut-off in some camera viewfinders and CCD chips. The Sony DCR-PC7 we use has very little cut off, so we prefer to use the 'Raw' settings of 720 x 480 (NTSC) and 720 x 576 (PAL) and interpolate them to 680 x 480 (NTSC) or 720 x 540 (PAL) in Adobe Photoshop.

A 'Custom' setting allows images to be interpolated up to 1024 x 768 pixels but there is little point in selecting any size bigger than the number of pixels in the camera - you can't fake real resolution. Even after downward interpolation to square pixels, PAL video cameras have 25% more pixels than 640 x 480 digital still cameras.

The final control sets de-interlacing, to reduce the motion artifacts between the two 'fields' (half 'frames') which are interwoven to make up a television 'frame', or picture.

A full resolution television frame is made up of two half frames, or 'fields', each composed of the odd- and even-numbered lines of a complete 525 line NTSC frame. There are 30 frames per second in a 525 line picture, made up of 60 fields per second to avoid flicker being noticeable. Outside the USA and Japan, many countries use 625 line PAL frames, made up of 50 fields per second. When the subject is in motion, it will have moved slightly between the first and second fields, resulting in comb-like edges. This can be avoided by eliminating one of the fields completely and duplicating the other, though this halves the vertical definition. In practice, however, this is hardly likely to be noticeable. PhotoDV has some settings which interpolate just those parts of the image which have moved. Canon have a new camcorder - the Optura - which has a progressive scan CCD 'Photo Mode' to avoid the problem. This market is changing fast.

When you find the precise frame (or field), it takes less than two seconds to capture it into the computer by FireWire. The system is so simple, so effective and so fast to use that it makes you never want to go back to using a low resolution digital still camera with slow serial interface.

Radius PhotoDV is only available for fast PCI Macs. It is an excellent product which costs $447.95, including FireWire card which can also be used for other purposes.

HOW DO THE ALTERNATIVES STACK UP?

By way of comparison, we photographed a still-life set-up of brightly colored model cars in four ways, to show what is achievable.

First we used a ten year old analogue Sony CCD-V90E camcorder such as

the one you might have in the cupboard. It records on Video 8 format.

The image was acquired using Play Incorporated's 'Snappy'. The

results are slightly smeary, with low colour saturation and a magenta

Paramount car. This is not the fault of Snappy, it's just the Video 8

showing its age.

Next we used a Sony DCR-PC7E Digital Video camcorder - not the best available but reasonably priced and certainly one of the sexiest. This camera would fit in a pocket and was one of the first to offer direct digital output via a FireWire socket on the camera. The images from this camera are bright and sharp.

By way of comparison, we used the popular Fuji DS-7 640 x 480 pixels digital still camera, framing the same shot using the camera's LCD screen. The image was acquired into a PC using a serial cable. Resolution is not quite as good as the DCR-PC7E, though the colours are slightly more saturated.

We

also used another 640 x 480 pixels digital stills camera, the Agfa

ePhoto307, which does not have a LCD screen or the ability to focus

close. We framed the image in the optical viewfinder and even allowed

for parallax - the offset between the viewfinder and lens. Unlike

shooting with the other three cameras, we didn't know what we'd got

(or hadn't got) until we pulled the pictures into the computer using

a serial cable. This camera produces good pictures at a distance but

shows the drawback of not having a LCD screen. (Newer Agfa cameras

have rectified this omission.

We

also used another 640 x 480 pixels digital stills camera, the Agfa

ePhoto307, which does not have a LCD screen or the ability to focus

close. We framed the image in the optical viewfinder and even allowed

for parallax - the offset between the viewfinder and lens. Unlike

shooting with the other three cameras, we didn't know what we'd got

(or hadn't got) until we pulled the pictures into the computer using

a serial cable. This camera produces good pictures at a distance but

shows the drawback of not having a LCD screen. (Newer Agfa cameras

have rectified this omission.

Detailed enlargements of the above images are unmodified and show just how the equipment actually performs.

Left: Sony CCD-V90E Analogue Camcorder Center: Sony DCR-PC7E Digital Camcorder Right: Fuji DS-7 Digital Camera

We used Adobe Photoshop to improve contrast, color balance, saturation and sharpness as one would normally do for print reproduction:

Compare these 'tweaked' versions with the unretouched versions of

the

Left: Sony CCD-V90E Analogue Camcorder and

Right: Sony DCR-PC7E Digital Camcorder

Testing the Sony digital camcorder outdoors. The image below is a photograph shot in the Cotswold area of England using the Sony DCR-PC7 digital camcorder. For high-resolution print magazine work, this shot might be a bit grainy at this size, but it is more than adequate for newspapers, and even at a 133 line screen it is passable. Obviously, it is more than sufficient quality for posting to the Web.

A Cotswold scene showing the selected test area on the right (boxed)

Left: Composite Video Centre: S-Video Right: Radius PhotoDV

Note the area outlined by the white rectangle in the bottom right corner. The image has been captured from the camcorder in three ways, and in each case, the outlined section has been enlarged considerably to show the differences in quality obtained by the three methods. The left detail was acquired by the normal 'composite' (NTSC or PAL) video signal. Note the noise (grain) and fuzziness in the red, bleeding around the wheel arch. The middle detail acquired using an S-Video cable. Note the noise (grain) in the red. The right detail was acquired using Radius PhotoDV and FireWire. Looking closely, one can detect cleaner color and higher resolution, despite the reduced amount of video processing compared with the Composite and S-Video outputs. The examples illustrate the superiority of FireWire over older methods of capturing video signals.

IN CONCLUSION

Although it is possible to grab pictures from your old camcorder or VHS tapes, the images will be much softer than from a DV camcorder. And don't expect any camcorder - including DV - to match the quality you get from a 35mm film camera. Video pictures just do not have that amount of detail in them.

However, digital camcorders used with FireWire produce stills as good as 640 x 480 pixel digital still cameras. They are fast to use and offer many additional features, making them eminently suitable for shooting still images for the web.

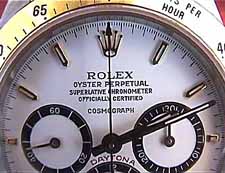

Sharp on close-ups. This image, taken with a Sony DCR-PC7 digital camcorder, illustrates how the zoom lens and electronic viewfinder enable the photographer to shoot tight close-ups that look good in print and on the Web.

THE FUTURE

Another application of DV is the ability to edit moving images easily on the desktop and to include these in websites and multi-media presentions. Radius are already shipping a 100% digitial non-linear DV editing system, EditDV, for $739.95.

The upsurge in interest in home theatre, with large screen tvs and video projectors, may bring about a demand for high definition camcorders, intended mainly for wealthy enthusiasts. Such camcorders would bring us much higher resolution pictures than are possible today.

Keep watching this space.

FEATURES TO LOOK FOR IN A DV CAMCORDER

Color LCD viewfinders - not one but two - are a must to ensure that what you see really is what you get. First, a monocular viewfinder, into which you look with one eye, for use in high ambient light conditions. If you wear eyeglasses, look for one with an eyesight correction adjuster. Second, a larger swing-out screen, which switches on when you fold it out from the camera. This can be twisted to any angle and also turned right over to give a right-way-up picture which can be viewed from in front of the camera. Also useful for taking hand-held overhead shots, or shots from low-angles.

Lens with a 10x optical zoom range with macro facility. Beware of outlandish claims for '40x' or '120x' as these are electronic range extensions which simply enlarge the central pixels, resulting in poor quality. If you need to do this, use a supplementary telephoto attachment - or crop in Photoshop. Macro is usually available only at the wideange end of the zoom. For even wider angles, buy a supplementary wideangle - or fisheye - attachment. Canon's new XL1 DV camcorder has an interchangeable lens mount system and will also take Canon EOS 35mm camera lenses.

Direct FireWire output. All Sony cameras have this but beware - although the earlier JVC DV-1camera recorded on DV it did not have FireWire output.

Exposure control. Video cameras have a standard shutter speed of one sixtieth of a second (NTSC) or one fiftieth (PAL) which is not fast enough to stop motion. Some cameras enable you to select faster electronic shutter speeds. Control of f-stop is only available on the near-professional cameras, though exposure lock and backlight controls will help preserve exposure settings in difficult lighting conditions. Low-end digital still cameras give no manual control over exposure.

Still picture function. Most camcorders now have a still picture or photo mode, which captures a single image and allows you to record it for a few seconds, with an accompanying burst of sound. Some cameras have built-in flash, or flash sync connection, to use in conjunction with this. But single frames grabbed from a rolling camera are just as good - and you get more to choose from.

Price. DV camcorders are state-of-the-art and cost a premium over the old VHS or Video 8 variety. But the pictures from them are so much better that they are worth every penny.